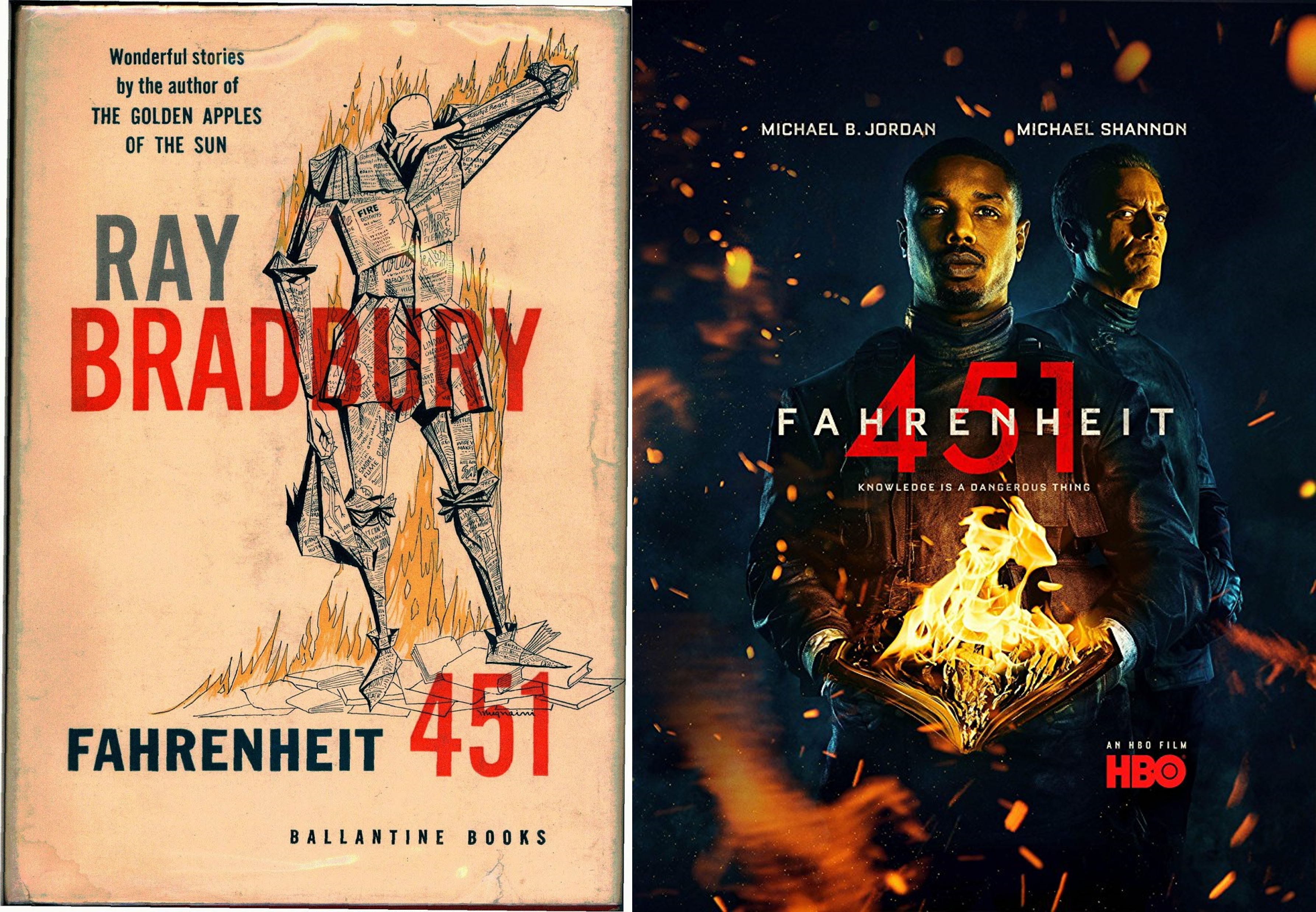

When I was in high school, we all had to read Fahrenheit 451 in 9th grade. Back then, there was always a problem I had with the book, and that was the fact that books and other paper products don’t actually burn at 451 degrees Fahrenheit. They burn at 450-451 Celsius, which is about 842 degrees Fahrenheit. It might seem like a nitpick, but I think it speaks to a much larger problem with the book. Namely, the fact that Ray Bradbury was a crusty curmudgeon who didn’t know what he was talking about.

Fahrenheit 451 has a lot of qualities I like to call “accidental merits,” meaning that the book actually does have a lot of good things in it that make it worth reading. These include the predicted atomization of the populace of the dystopian society, the constant bread and circuses nature of their culture, and the horrifying nature of the robotic “hound” that replaced the fire station’s more traditional dalmatians, the last of which being more like a robot in a dog-skinsuit, which the fire fighters are told to just accept is a normal dog. But the main point that Ray Bradbury was aiming at when he originally wrote the Fireman as a short story that would later become the book, were not how things like censorship are bad and how books are harder to censor, but rather that this dang newfangled television was going to ruin society and the youths were spending too much time watching TV and listening to music. One way you can mock the ever-loving hell out of him is to listen to Fahrenheit 451 on your headphones.

Okay, I need to be fair: unlike his short story the Fireman, there is a point where Ray Bradbury has enough self-awareness to point out that it isn’t the medium of books that is so special. TV is only bad when it only contains mindless entertainment that doesn’t engage your brain. The problem with books is that they don’t work at all if you aren’t using your mind to imagine the things you read about. I have never heard someone say “just turn your brain off” to get through a stupid book; I’ve heard people use that same slogan repeatedly to get me to watch and enjoy terrible movies that I know are a waste of two-three hours I’ll never get back.

That said, there is something about books that distinguishes them from audiobooks. Reading a book takes time and actual work in making yourself read the words on the pages. Listening to an audiobook can be an act of multi-tasking, and it takes no effort other than to listen to the book being read to you. Actually reading the book does have some different impact on your brain than just listening to it.

I think this is part of the reason why people are always saying whenever a new movie comes out that “the book was better.” There is a feeling of accomplishment that you get from finishing a book that isn’t there when you listen to an audiobook. This has gotten me thinking if some forms of media truly are superior to others. Or, what advantages exist in consuming media in some forms that aren’t available in others?

Live-Action TV is perhaps the most obvious. The advantage of this medium is that no imagination is required to understand exactly what the creator had in mind when they invented their story. To a certain extent, live-action film falls in here as well, but with the clear distinction that a movie is meant to be a longer story that has to be condensed into a single, 2-3 hour session, whereas a show can be longer, but there is an expectation that the individual stories be a lot shorter.

Some people will always insist that books are superior to Live-Action TV, and I can’t shake the sense that this is mostly due to snobbery. It is true that by an objective measure, there are reasons why the book of a story will often be better than the movie. First, a book is often written by a single author with a single vision, or occasionally two or more writers, while a movie or a show requires a team of chefs that can easily spoil the soup. Second, the version of events that plays in your head when you read a book is always going to be tailored to your imagination, while the silver screen version of the story is crystalized, and cannot be debated. There will be things in a book that can be up to the audience’s interpretation that cannot easily translate into a show.

But all of this aside, there are plenty of examples where the film or show of a book turned out better than the original. Ignoring the last two seasons when they ran out of books, Game of Thrones was actually much easier to follow than A Song of Ice and Fire, because George R.R. Martin really needs an editor. The film version of The Princess Bride is an even better example, because the book is little more than a by-the-numbers story about a princess in a light-fantasy world being rescued by her pirate-lover and packed with boring worldbuilding nonsense that no one cares about (and why no one today reads the book). The film, however, is instead about a grandfather passing down a story to his grandson and deliberately skipping all the parts the kid wouldn’t want to hear (hence why there’s so many kissing scene jokes).

There is something worth noting about TV at the time Ray Bradbury wrote Fahrenheit 451. VCRs hadn’t been invented yet, and while there were things like film reels, most people couldn’t own them or play them on a projector screen in their own homes. There was no such thing as a show you could watch at your leisure; you had to watch your favorite programs as they aired. This meant that when it came to entertainment, your broadcasting company had full control of what you watched and when. And since this was during the Cold War, many countries had governmental control on what was allowed to be on the air, including the U.S., and there was a lot of propaganda and regulation. This, combined with the fact that TV is much better than books at getting people to feel certain emotions, in particular when music is applied, makes TV a much more useful tool for propaganda than books, especially since books require you to think, and that’s usually something propagandists want you to avoid. Comparing this to how streaming services have been known to pull shows and movies or edit them for “modern audiences,” and we can see that things have come full circle.

A lot of people will note that Fahrenheit 451 is one of those books that actually became more relevant after it was written. This is why we can laugh at Ray Bradbury for whining about kids with their dang new technology, but also learn a lot from his writing because, intentionally or not, he stumbled upon something bizarrely relevant in a weird spark of genius. Or a spark of insanity. Sometimes they’re the same thing.

Animation is an even stranger medium because, in some ways, it can bring some stories to life better than live action. The Lion King might be one of the best examples, since the color schemes of the animated movie make characters like Pumba and the lions easier to see, because a real warthog and other animals have camouflage designed to make them blend in with their surroundings. This is one of the many complaints people have about the live action remake. Another example is the way light works in water. We can watch an animated film like the Little Mermaid and have the setting drawn in a way that doesn’t make it hard for our eyes to see in the dark depths of the ocean, but because the film is animated, the bright colors and high visibility don’t take us out of the story. You can apply this logic to science fiction stories that take place in space as well, although most people don’t know how light works in space anyway, so live-action TV can get away with more things there than they can with the ocean.

Theater is a bit of a weird, because although we think of it as a visual medium, it originally wasn’t. Back in the days of Shakespeare, you didn’t say “let’s go see a play.” You instead would say “let’s go hear a play,” because it was understood that a bare stage with minimal costumes was just part of the show. In the Globe Theater, Shakespeare put on plays with very little in the way of scenery or visual effects, even though a variety of options were available, because the understanding at the time is that the audience was mostly there to hear the play, not to watch it. The Globe Theater itself is even designed acoustically to ensure that the audience can hear the play from any seats in the house, but many seats are actually facing to the side of the stage, or in places where it would be difficult for folks to see the play.

What distinguishes theater from having someone read a book aloud to you is mostly in the actors and they’re ability to perform the play lines with their acting. If you’ve ever heard an audiobook where the voice actors go out of their way to act out the parts of the characters they’re voicing, you kind of have an idea of what I mean. This is different from how plays are often performed now, with more emphasis on the visuals. Musicals are a bit different in that, usually, it is understood that the songs and dance numbers are not actually taking place in the story, but the intent that people are there to hear the story more than they are to watch it is still there, to some extent. This is why movie versions of musicals, like Les Misérabes, have trouble with scenes wherein there isn’t anything happening on stage/screen to show the audience (see the scene where Fantine has to prostitute herself, and the cameraman clearly has no idea what he’s supposed to be focusing on). In the musical, that wasn’t something the audience had to see in order for the show to work.

Am I going to talk about video games as a medium? Eh, not today. They deserve a blog post entirely to themselves, and there’s not much I could say in this final paragraph about them that hasn’t already been said by Extra Credits.

In sum, I do not believe there is such a thing as a “superior” medium when it comes to storytelling. They all have their strengths and weaknesses, and if someone always insists that “the book was better,” they might be right, but they might just be a snob.