Something I’ve noticed a lot lately is that a lot of modern media, particularly fantasy and historical dramas, have a tendency to throw in elements that people immediately question as “not believable,” even though they might take place in a world with wizards and elves. And the response creators have to this is usually something like “what, you’ll accept wizards and goblins but you won’t accept black people in northern Medieval Europe?”

Well, yeah, actually.

Verisimilitude is technically defined as “the quality or state of being verisimilar.” Since that’s an absolutely useless definition, let’s look at the definition of verisimilar, which in art or literature is “depicting realism.” For the purposes of media, verisimilar works are shows that feel realistic, or feel like people could actually live there. It might even include having the characters act like a reasonable person would if they lived in those conditions.

For example, if you’re watching a show where magic is confirmed to exist and spells are common enough that everyday people recognize that they exist, it would be reasonable for everyone to believe in magic, and possibly to even go to fortune tellers, or other street peddlers we would call charlatans in real life, because they have some evidence that at least some magic works, even if tarot cards don’t.

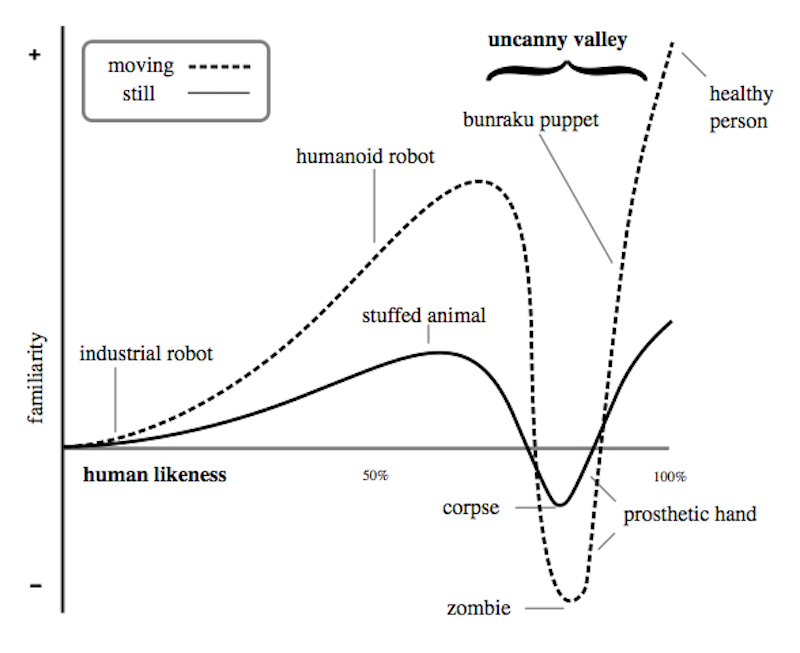

What I’ve discovered recently is that there’s an overlap between verisimilitude and the uncanny valley. The uncanny valley, for anyone who doesn’t know, is the relationship people have to things that we recognize and have a context for and how things that seem slightly “off” to us invoke a sense of revulsion, discomfort, or even horror instead of familiarity. For example, a humanoid robot with a smiley face might be thought of as cute, or funny, but a humanoid robot that has a somewhat human-looking face will bother people, since it won’t look exactly like a human. The uncanny valley is best thought of as the place where an object becomes so similar to what we have a context for in real life that people stop noticing what’s familiar about the object, and start highlighting what’s unfamiliar.

Imagine a lamppost on a dark street at night that has a flickering light bulb. If the light would stay on and stop flickering, you wouldn’t notice, as your brain would think it was normal. If the light was completely out, your brain would assume that the street corner simply didn’t have any power at the moment, and might not be in use. But a flickering light bulb means A) there is still power being sent to the lamppost and B) the lamppost isn’t being well maintained, or the power supply isn’t stable. Either way, something about it just seems “off” to you.

Now think of a story you’ve read or seen on TV lately, where something felt off about the way the world was constructed. Maybe it was a recent fantasy story that had an excess of ethnic diversity in Medieval Europe. Maybe it’s a fantasy setting where 25-50% of the characters were LGBTQ+. Your brain doesn’t have a context for magic, or other fantastical elements of the story, and as a result you don’t get a sense that something is “off” about these elements. Part of this is because magical wizards and monsters are never presented to the audience as “depicting realism.” But your brain notices the impossible ethnic diversity, which your brain actually does have a context for, and thinks “hang on, how did a black man get all the way up to France in a time when we had very little in the way of transportation? Is he a noble who could afford the high cost of travel back then? Doesn’t that mean that his home, estates, and other sources of wealth are all located back in the country he came from, meaning he will eventually have to return there to govern the place? Is he a pilgrim, or a traveling merchant? That would at least make sense, but he wouldn’t be integrated as a fixed or permanent member of the culture.

In real life, you would need a massive group of people immigrating from one part of the world to another in order for them to form families that retain their ethnic features over generations; a lone black man moving to Europe and staying there is only going to have kids with a white woman, and after a few generations his descendants will look like other white people.

A similar problem shows up whenever you read a book or watch a show with an unusually high number of LGBTQ+ characters. On some level, everyone knows that if LGBTQ+ people made up a significant percentage of the population, it wouldn’t be long before there would be no population. That’s why whenever you see such a thing in a work of fiction, your brain immediately tells you something is “off.”

There are other ways a lack of verisimilitude can trigger the uncanny valley response in your brain. If the magic system you’ve created allows people to perform incredible feats with minimal effort on the part of the mage, readers are going to wonder why there is any conflict in your world. We learn in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire that the Weasley family can rent a tent that’s bigger and more luxurious on the inside than their actual house. The Weasleys are shown in universe to always be struggling financially, but the abilities we see with things like magic have made plenty of readers wonder how that could be possible. Between the dishes that wash themselves, broomsticks that are faster and more efficient than any car and don’t need gasoline or car insurance, and spells that allegedly cannot create food, but are shown to be able to make existing food bigger, it’s almost impossible to believe that this family of godlike wizards could be poor, and even if you didn’t notice this while reading the books or watching the movies, your brain certainly did.

What seems to really trigger the uncanny valley response in people is when something is presented to the audience as if it should be accepted as realistic. When a show displays a fantasy world with an excess of LGBTQ+ people and doesn’t pretend that this is normal, or even acknowledges that these people are flocking together to form their own community, we can still accept it in the same way we can accept magic in a fictional setting, because we know it’s fiction. But when a show tries to pass such things off as if they’re actually real, or might have happened in the real world, the human brain senses that something is wrong. It’s this false verisimilitude trying to pass itself off as the real thing that triggers uncanny valley reaction.