Here’s a question: when was the last time you saw a movie you wanted to see again? Not right away; I mean a film so good that you could enjoy rewatching it with a different crowd of people? If you think about it, I’d be willing to bet that you haven’t seen very many movies lately that you could enjoy rewatching.

Now let me ask you this: how many films from the 80s and 90s do you enjoy rewatching even now? How many times have you seen Die Hard, or Jaws, Minority Report, Blade Runner…and the list just keeps going. Sure, you might have enjoyed seeing a modern movie now and then; even on a bad year, there’s always at least one gold nugget amongst the turds. But there’s a thing called “rewatchability” that’s missing from a lot of modern stories today.

This doesn’t just extend to movies. A lot of other media, like TV shows, and even books, just doesn’t make you want to consume it a second time anymore. People still reread copies of books like Harry Potter and The Lightning Thief today, but when was the last time you saw someone read a book that was published recently more than once? Can you remember a time you consumed the same media a second time, maybe to look for clues you might have missed the first time, or maybe just to recapture the fear/joy/inspiration you got out of it the first time?

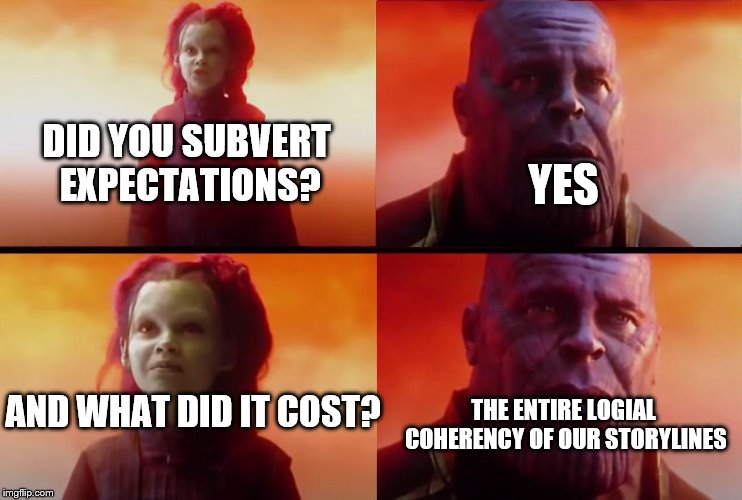

Some of this is due to the modern world having too many things demanding our attention, but I don’t think that explains why people are still rewatching the original Jurassic Park, the original Star Wars Trilogy, or The Princess Bride to this day. I think there’s something about older media that’s just missing from newer stories. And I believe that the main problem is how much people focus on trying to subvert their audience’s expectations.

See, after the Internet initially devolved into a cesspool of social media bullying platforms, online piracy, and porn, lots of porn, things started to cool down in the late 2000s and people started creating blogs where they could post fan theories on upcoming movies and TV shows. And when some of these theories about how their favorite media stories were going to turn out were proven correct, a lot of writers responded by rewriting their story plans so that they’d be something other than what people had originally guessed, even if their new story endings didn’t make any sense.

Something of an arms race developed in which audiences tried to predict how shows and movies were going to end, even for films that were advertised but hadn’t come out yet, and the writers would try to stay one step ahead of their fans. At no point did the writers think “maybe I should congratulate my fans for guessing correctly,” or “some of my fans are going to be smarter than other fans. If they guessed the ending of my story correctly, maybe that’s a sign that the clues I placed in earlier episodes functioned as intended, and I shouldn’t try to trick the audience.” Instead, writers stopped setting up the stories’ actual endings, leaving red herrings, fake clues, and left audiences with payoffs that made no sense.

Alfred Hitchcock once explained that it doesn’t matter if the audience knows the basics of what is going to happen in the story; all that matters is that people enjoy the story as it unfolds. For example, if there’s a bomb under a table in a restaurant, and the audience knows about it, but there are a lot of characters in the restaurant who don’t know about the bomb, it doesn’t matter that the audience knows the bomb will go off. What matters is the suspense in wondering which characters will make it out alive while the viewers are waiting for the bomb to explode. It’s the suspense, not the surprise, that makes a good story. If the bomb fizzled out and didn’t go off, and instead aliens blasted the restaurant from space, your audience will be surprised, but that doesn’t mean they’ll be satisfied.

What bothers me most about this focus on subverting expectations fad is that it seems to be so important to some creators that they’re willing to violate just about every other rule around good writing. Sure, some rules are made to be broken, but that doesn’t mean they can be ignored all the time. For example, setup and payoff: you’re supposed to arrange things to that if there’s an important event that will happen in the future of the story, you’ve got to leave clues to the audience about it ahead of time. In a way, this is meant to invoke cause and effect; we see a clue, and that clue tips us off to an event that will happen later.

Another rule that gets ignored to subvert expectations is the Chekhov’s Gun. Chekhov’s Gun dictates that if a gun is described in detail in chapter 1, it is to be expected that the gun will be fired (or at least play some role important to the plot) by chapter 4. It’s pretty flexible, but the point is not to waste the audience’s time on details that aren’t going to be important later. If you’re trying to subvert their expectations, wasting the audience’s time is often part of the goal, not the terrible sin of writing that it should be seen as. This just leaves the audience rightfully upset that they’ve been tricked.

Now, there is a corollary to all of this: subverting old tropes and story plots by having them play out in a way that’s more realistic than they’re normally shown. For example, when the nerdy hero tries to impress his crush, wins some big award, and it doesn’t actually convince the girl to go out with him. That’s more of a deconstruction than a straight-up subversion. There’s nothing wrong with writing stories that examine how things would realistically play out, and that doesn’t need much setup in order to work. Real life outside of the book/movie/show is enough of a setup that you don’t need anything else.